About Scout Scar: Looking into a Cumbrian Landscape

By Jan Wiltshire

|

Book details

or by visiting www.carnegiepublishing.com About Scout Scar. I continue to write about Scout Scar and locations featured. There's a search facility (top right). Enter the location you seek, or a topic. Looking for a season? Try the archive on the blog page. See images of flooding in the Lyth Valley the day after Storm Desmond in December 2015. Or butterflies on Scout Scar during the heat-wave summer months of 2018. See Foulshaw Moss as the osprey return to breed in 2019. |

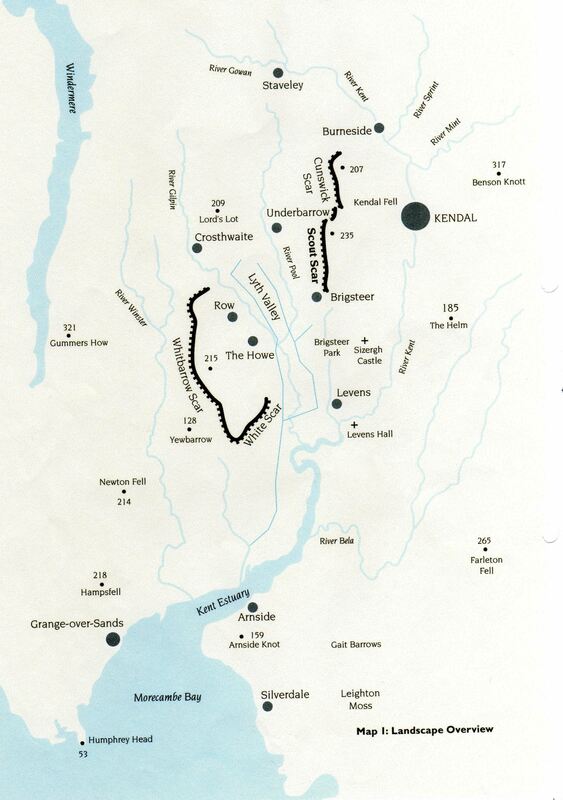

Map and landscape overview copyright About Scout Scar 2008

From About Scout Scar, landscape overview

On its swift, short course to its estuary at Morecambe Bay the River Kent flows through the market town of Kendal which is situated on the north-eastern edge of a belt of limestone hugging the volcanics of the central Lake District. The Kent estuary penetrates these Morecambe Bay limestones , the character name by which the area is known, and there is a diversity of limestone features including a series of escarpments; Hampsfell, Yewbarrow, Cunswick Scar and Scout Scar, the latter being about two kilometres west of Kendal. Each of these escarpments has a north-south alignment, with its scarp slope facing west, its dip slope to the east.

This area of carboniferous limestone was subject to the scouring of glaciation during the Ice Age. Limestone is permeable and fast-draining, due to its network of open joints, so once the last of the ice had retreated and the permafrost had gone there was little further surface water erosion. The dry valleys which characterise the landscape would have been deepened during the period of glaciation. There is little standing water on these uplands and the aerial view shows outcropping bands of rock above the cliffs of the Whitbarrow scarp and extensive exposed limestone on the broad ridges of Whitbarrow and Scout Scar. This often occurs as frost-shattered rafts of clitter, conveniently to hand for the building of the dry-stone walls whose signature is the sharp edges of its pure white limestone and the grey and black lichens associated with this alkaline rock. The glaciers transported much debris, including weighty objects and, as the ice melted, deposited them onto the scoured limestone bedrock so that a boulder of alien rocks sits on a limestone plinth, like a sculpture. These glacial erratics have bright lichens that indicate acid rock. Glaciers dumped their boulders but carried finer debris out to Morecambe Bay, and silts and sands were blown onto Whitbarrow and Scout Scar to form pockets of loess in dips and hollows of the limestone. In these acid soils heather grows and offers shelter and a micro-habitat.

At 235 metres Scout Scar is marginally higher than Whitbarrow (215 m) and Hampsfell (218m) but each offers magnificent views of the surrounding countryside.

These ridges and escarpments are exposed to the prevailing south westerlies which, on Whitbarrow especially, create wind-blasted yew trees that resemble dark pennons. With no standing water, poor soils and lack of nutrients, scattered trees grow stunted amongst rafts of limestone clitter and there are native juniper, yew and hawthorn on the broad ridges.

Whitbarrow

Whitbarrow- the white hill- and to the south the dramatic cliff of White Scar. In sunlight, light bright Whitbarrow. There are a few clusters of larch and birch but it is an open ridge with blue moor grass, a spring and summer flush of limestone flora and a wealth of butterflies. Sections of the cliffs and screes of its scarp slope are concealed by hanging woods. On gloomy days, these limestone escarpments have a somewhat forbidding appearance with dark yew rooted in fissures in the rock face, and Black Yews Scar, below Lord’s Seat, is an evocative name. East of the viewpoint of Lord’s Seat, the dip slope is broken by a series of minor stepped limestone scarps with yew and juniper rooted into the rock and swept and sculpted into strange shapes. And above each shallow cliff there is a shelf of limestone pavement with clint and gryke formation. Hampsfell and Whitbarrow have open and wooded limestone pavement , a habitat of which scout Scar has only vestigial traces. Hidden within the trees on Whitbarrow is Gillbirks Quarry which provided building stone for Kendal. Farms, and the famous damson orchards of the Lyth Valley, are situated low on the sheltered dip slope at the spring-line where permeable limestone is down-faulted against impervious Silurian slates and greywackes. The hamlets of Row and The Howe are surrounded by an intake wall and fields whose old boundaries have all the quirks and irregularities of an English landscape.

The Lyth Valley

Between the limestone escarpments of Whitbarrow and Scout Scar lies the Lyth Valley. Its river, the Gilpin, has its confluence with the River Kent almost at its estuary as it debouches into Morecambe Bay. Looking down upon its broad flood plain from Scout Scar, it still resembles an inlet of the sea, with White Scar, the cliff at the southern tip of Whitbarrow, a headland looking out over the bay. The topography suggests it and winter flooding highlights this impression as the eye scans across flooded pastures and out to sea.

When sunlight gleams on flood waters the pattern of the comparatively recent man-made landscape is emphasized and there is a geometric and angular look about the network of roads and fields, each bordered by hedge and drainage ditch. With deep ditches on either side, roads are often elevated and hump-back bridges span drain and river. From the height of Scout Scar the grassy embankments of Underbarrow Pool show clearly. Drainage in the Lyth Valley has layers historical and physical, with a higher system and a lower system that channels water underneath the river. A nexus of drains and ditches converges on the pumping stations on which agriculture in the valley depends. There is a handful of rocky knolls and outcrops dignified with the name of hills. Dobdale Hill is shown on the OS map at 10 metres, a single ring contour, whilst High Heads has a spot height of 24 metres. Farmsteads are situated on the limestone where it meets the moss. Cinderbarrow is at an elevation of 20 metres, just south of the wooded scarp slope of Brigsteer Park. Park End Farm is at 30 metres.

When these older farms were built the Lyth Valley was an area of wetland, a raised bog drained only by the ditches of the peat workings. The River Gilpin was tidal and reached as far as Underbarrow, depositing sand with each tide. The essential wetland nature of the Lyth Valley is declared on the OS map by the numerous mosses, drains, dikes and ditches. These peat mosses were a source of fuel for Kendal but by the end of the 19th century the town was no longer dependent on the peat which was gradually being worked out. Park Moss, on the flood plain below Brigsteer Park, was well placed to supply Sizergh Castle with fuel. Peat was stored in peat cotes and Cotes is shown on the OS map just below the limestone scar bank at Levens, where peat cutters lived. At Row, on the western side of the valley, there is a peat house built mid-18th century as a peat store for the farm, now a holiday cottage.

The appearance of the Lyth Valley landscape was transformed early in the 19th century with the reclamation of the mosses subsequent to the Heversham Enclosure Act and Award. A comprehensive drainage system was introduced and the main drain through the centre of the valley dates from that time. Catchwaters were dug to divert spring water from the slopes of the valley: the western catchwater is a drain to collect run-off from the dip slope of Whitbarrow and pump it out to sea. The eastern catchwater runs below Brigsteer Park where the wooded limestone scarp slope meets peat at Park Moss, continuing past Cotes and Levens to empty directly into the River Kent. The mosses were drained, birch trees began to colonise, and across the Lyth Valley there are pockets of birch and oak woodland. Wetland habitat was lost and with the acidic peat removed there was a black, alluvial soil with blue clay close beneath. To prepare the land for arable farming, quantities of lime were spread and there are numerous lime kilns, like the cluster about Row low down on the Whitbarrow dip slope, where limestone was readily available to process for use as a fertiliser during the reclamation of the mosses. The pattern of the Lyth Valley fields and their encompassing ditches dates from that time, the geometric design made possible by the flood plain. Near Coates, off Quagg’s Road, there is a cluster of narrow field strips which were rights of common of turbary where a household worked its peat. Roads were laid over the mosses and, like the sequence of Moss Lanes in the vicinity of Tullythwaite Hall, they attempt to provide access to all the fields. Today, there is little arable farming in the valley. At Lord’s Plain, a significantly low-lying farm built shortly after enclosure and the reclamation of the mosses, they graze sheep and rear black and white Holstein Friesian cattle. The farm is a tenancy of the Levens Hall estate. At Cinderbarrow Farm, they have a dairy herd of Jerseys and a thousand sheep. Over four kilometres to the north, at Tullythwaite Hall, they have Hostein Freisian dairy cattle. All these farmers make silage for their cattle. The farmers spread a ground and powdered limestone as a spring fertiliser but this is only applied once in ten or fifteen years. Ground limestone comes from a local quarry at Silverdale.

The pumping system copes, apart from exceptional rains when there is flooding, but the water doesn’t rise fast so there is no drowning, though when it is very wet sheep may have to be moved to fields less prone to flooding. With the construction of the A 590 dual-carriageway, doors were fixed beneath it at Sampool Bridge so the River Gilpin is no longer tidal and this makes maintenance of the drains and ditches somewhat easier. The maintenance regime accords with National Environment Agency directives: farmers must not plough or cultivate right up to the hedges and fertiliser must not be introduced into the ditches. At Lord’s Plain Farm they have 3 ½ miles of ditches to maintain and a contractor flails the hedges and mows out the ditches to give the water a free run. They are dredged every five years to clean mud out at the bottom.

The protection and restoration of wetland habitat, of aquatic habitat, in Cumbria and the Lyth Valley is encouraged by conservation bodies and there are already nature reserves at Foulshaw Moss, which is a peat bog- a lowland raised mire on the Kent Estuary.

Copyright Jan Wiltshire 2008

On its swift, short course to its estuary at Morecambe Bay the River Kent flows through the market town of Kendal which is situated on the north-eastern edge of a belt of limestone hugging the volcanics of the central Lake District. The Kent estuary penetrates these Morecambe Bay limestones , the character name by which the area is known, and there is a diversity of limestone features including a series of escarpments; Hampsfell, Yewbarrow, Cunswick Scar and Scout Scar, the latter being about two kilometres west of Kendal. Each of these escarpments has a north-south alignment, with its scarp slope facing west, its dip slope to the east.

This area of carboniferous limestone was subject to the scouring of glaciation during the Ice Age. Limestone is permeable and fast-draining, due to its network of open joints, so once the last of the ice had retreated and the permafrost had gone there was little further surface water erosion. The dry valleys which characterise the landscape would have been deepened during the period of glaciation. There is little standing water on these uplands and the aerial view shows outcropping bands of rock above the cliffs of the Whitbarrow scarp and extensive exposed limestone on the broad ridges of Whitbarrow and Scout Scar. This often occurs as frost-shattered rafts of clitter, conveniently to hand for the building of the dry-stone walls whose signature is the sharp edges of its pure white limestone and the grey and black lichens associated with this alkaline rock. The glaciers transported much debris, including weighty objects and, as the ice melted, deposited them onto the scoured limestone bedrock so that a boulder of alien rocks sits on a limestone plinth, like a sculpture. These glacial erratics have bright lichens that indicate acid rock. Glaciers dumped their boulders but carried finer debris out to Morecambe Bay, and silts and sands were blown onto Whitbarrow and Scout Scar to form pockets of loess in dips and hollows of the limestone. In these acid soils heather grows and offers shelter and a micro-habitat.

At 235 metres Scout Scar is marginally higher than Whitbarrow (215 m) and Hampsfell (218m) but each offers magnificent views of the surrounding countryside.

These ridges and escarpments are exposed to the prevailing south westerlies which, on Whitbarrow especially, create wind-blasted yew trees that resemble dark pennons. With no standing water, poor soils and lack of nutrients, scattered trees grow stunted amongst rafts of limestone clitter and there are native juniper, yew and hawthorn on the broad ridges.

Whitbarrow

Whitbarrow- the white hill- and to the south the dramatic cliff of White Scar. In sunlight, light bright Whitbarrow. There are a few clusters of larch and birch but it is an open ridge with blue moor grass, a spring and summer flush of limestone flora and a wealth of butterflies. Sections of the cliffs and screes of its scarp slope are concealed by hanging woods. On gloomy days, these limestone escarpments have a somewhat forbidding appearance with dark yew rooted in fissures in the rock face, and Black Yews Scar, below Lord’s Seat, is an evocative name. East of the viewpoint of Lord’s Seat, the dip slope is broken by a series of minor stepped limestone scarps with yew and juniper rooted into the rock and swept and sculpted into strange shapes. And above each shallow cliff there is a shelf of limestone pavement with clint and gryke formation. Hampsfell and Whitbarrow have open and wooded limestone pavement , a habitat of which scout Scar has only vestigial traces. Hidden within the trees on Whitbarrow is Gillbirks Quarry which provided building stone for Kendal. Farms, and the famous damson orchards of the Lyth Valley, are situated low on the sheltered dip slope at the spring-line where permeable limestone is down-faulted against impervious Silurian slates and greywackes. The hamlets of Row and The Howe are surrounded by an intake wall and fields whose old boundaries have all the quirks and irregularities of an English landscape.

The Lyth Valley

Between the limestone escarpments of Whitbarrow and Scout Scar lies the Lyth Valley. Its river, the Gilpin, has its confluence with the River Kent almost at its estuary as it debouches into Morecambe Bay. Looking down upon its broad flood plain from Scout Scar, it still resembles an inlet of the sea, with White Scar, the cliff at the southern tip of Whitbarrow, a headland looking out over the bay. The topography suggests it and winter flooding highlights this impression as the eye scans across flooded pastures and out to sea.

When sunlight gleams on flood waters the pattern of the comparatively recent man-made landscape is emphasized and there is a geometric and angular look about the network of roads and fields, each bordered by hedge and drainage ditch. With deep ditches on either side, roads are often elevated and hump-back bridges span drain and river. From the height of Scout Scar the grassy embankments of Underbarrow Pool show clearly. Drainage in the Lyth Valley has layers historical and physical, with a higher system and a lower system that channels water underneath the river. A nexus of drains and ditches converges on the pumping stations on which agriculture in the valley depends. There is a handful of rocky knolls and outcrops dignified with the name of hills. Dobdale Hill is shown on the OS map at 10 metres, a single ring contour, whilst High Heads has a spot height of 24 metres. Farmsteads are situated on the limestone where it meets the moss. Cinderbarrow is at an elevation of 20 metres, just south of the wooded scarp slope of Brigsteer Park. Park End Farm is at 30 metres.

When these older farms were built the Lyth Valley was an area of wetland, a raised bog drained only by the ditches of the peat workings. The River Gilpin was tidal and reached as far as Underbarrow, depositing sand with each tide. The essential wetland nature of the Lyth Valley is declared on the OS map by the numerous mosses, drains, dikes and ditches. These peat mosses were a source of fuel for Kendal but by the end of the 19th century the town was no longer dependent on the peat which was gradually being worked out. Park Moss, on the flood plain below Brigsteer Park, was well placed to supply Sizergh Castle with fuel. Peat was stored in peat cotes and Cotes is shown on the OS map just below the limestone scar bank at Levens, where peat cutters lived. At Row, on the western side of the valley, there is a peat house built mid-18th century as a peat store for the farm, now a holiday cottage.

The appearance of the Lyth Valley landscape was transformed early in the 19th century with the reclamation of the mosses subsequent to the Heversham Enclosure Act and Award. A comprehensive drainage system was introduced and the main drain through the centre of the valley dates from that time. Catchwaters were dug to divert spring water from the slopes of the valley: the western catchwater is a drain to collect run-off from the dip slope of Whitbarrow and pump it out to sea. The eastern catchwater runs below Brigsteer Park where the wooded limestone scarp slope meets peat at Park Moss, continuing past Cotes and Levens to empty directly into the River Kent. The mosses were drained, birch trees began to colonise, and across the Lyth Valley there are pockets of birch and oak woodland. Wetland habitat was lost and with the acidic peat removed there was a black, alluvial soil with blue clay close beneath. To prepare the land for arable farming, quantities of lime were spread and there are numerous lime kilns, like the cluster about Row low down on the Whitbarrow dip slope, where limestone was readily available to process for use as a fertiliser during the reclamation of the mosses. The pattern of the Lyth Valley fields and their encompassing ditches dates from that time, the geometric design made possible by the flood plain. Near Coates, off Quagg’s Road, there is a cluster of narrow field strips which were rights of common of turbary where a household worked its peat. Roads were laid over the mosses and, like the sequence of Moss Lanes in the vicinity of Tullythwaite Hall, they attempt to provide access to all the fields. Today, there is little arable farming in the valley. At Lord’s Plain, a significantly low-lying farm built shortly after enclosure and the reclamation of the mosses, they graze sheep and rear black and white Holstein Friesian cattle. The farm is a tenancy of the Levens Hall estate. At Cinderbarrow Farm, they have a dairy herd of Jerseys and a thousand sheep. Over four kilometres to the north, at Tullythwaite Hall, they have Hostein Freisian dairy cattle. All these farmers make silage for their cattle. The farmers spread a ground and powdered limestone as a spring fertiliser but this is only applied once in ten or fifteen years. Ground limestone comes from a local quarry at Silverdale.

The pumping system copes, apart from exceptional rains when there is flooding, but the water doesn’t rise fast so there is no drowning, though when it is very wet sheep may have to be moved to fields less prone to flooding. With the construction of the A 590 dual-carriageway, doors were fixed beneath it at Sampool Bridge so the River Gilpin is no longer tidal and this makes maintenance of the drains and ditches somewhat easier. The maintenance regime accords with National Environment Agency directives: farmers must not plough or cultivate right up to the hedges and fertiliser must not be introduced into the ditches. At Lord’s Plain Farm they have 3 ½ miles of ditches to maintain and a contractor flails the hedges and mows out the ditches to give the water a free run. They are dredged every five years to clean mud out at the bottom.

The protection and restoration of wetland habitat, of aquatic habitat, in Cumbria and the Lyth Valley is encouraged by conservation bodies and there are already nature reserves at Foulshaw Moss, which is a peat bog- a lowland raised mire on the Kent Estuary.

Copyright Jan Wiltshire 2008

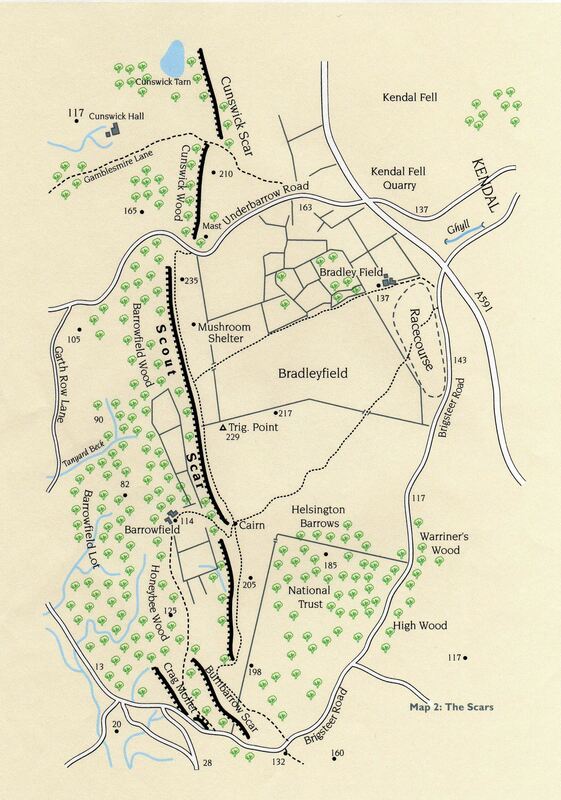

Map from About Scout Scar showing Kendal Fell, Cunswick Scar, Scout Scar