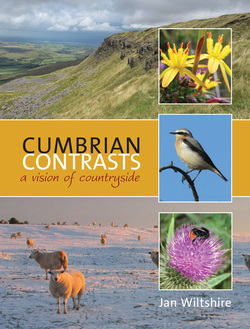

Cumbrian Contrasts, A vision of countryside

By Jan Wiltshire

|

Paperback 96 pages. 120 full colour photographs. Publisher Palatine Books February 2016

ISBN 978-1-910837-30-0 Book dimensions 19 cm x 24.8 cm Cumbrian Contrasts can be ordered direct from the publishers on 01524 840111 or by visiting www.carnegiepublishing.com £ 12.99 'Cumbrian Contrasts is beautiful, inspiring and informative. It offers a new perspective on Cumbria that will appeal to all who love the Lakes. Celebrating the wonder of the natural world, it’s a snapshot in time, a portrait of now that reflects on the past and looks to the future. Author Jan Wiltshire is a talented writer and a keen naturalist, dedicated to conservation. Her stunning new book draws us to look closely and to cherish all that we discover.' |

1 Introduction

An hour after midnight twelve children made their way through the town heading for Scout Scar. They left the last of the houses behind

’there burst upon us, all unforeseen, such a ‘festival chorus’ of larks as no one of us had ever heard before. On all sides, unseen in the gray dimness, they sang as if their little hearts could hold no longer the rising flood of music, and they must needs shake it out anyhow, anywhere, with splendid unthrift, above the gray sleeping world.’ *

As the stars faded away they reached the escarpment and waited for sunrise. But lark song was the surprise and wonder of that midsummer morning in 1906.

As a naturalist, my focus is on our experience of countryside, then and now. These children give us a glimpse of how it was. 2014 saw commemorations to mark the centenary of the outbreak of The First World War, 1914-18. Throughout the year in a constant refrain, media coverage reflected on life in Britain a hundred years ago. I wrote the core of Cumbrian Contrasts in this context, with a heightened awareness of history.

Late in 2013, extensive building programmes for Kendal and Ulverston were unveiled. Change was imminent. The character of Kendal would change and so would the countryside on its doorstep.

I’d like the children of today and tomorrow to be surprised and delighted by lark song and the call of the cuckoo. I hope that may be part of their experience but both species are in dramatic decline and there’s nothing to protect the ground-nesting birds of Scout Scar. Save the skylark, that’s the watchword. The bird is an emblem of species-loss.. For wildlife and countryside everywhere we all have a part to play.

Cumbrian Contrasts celebrates the wonder of the natural world. It’s a snapshot in time, a portrait of now that reflects on the past and looks to the future.

Like those children, I walk from Kendal and head for Scout Scar. Venturing beyond, I radiate out across Cumbria excited by the prospect of all I might discover.

*Lucy M Reynolds, Sunrise on Scout Scar, from Stramongate Quaker School Magazine, September 1906.

2 Kendal: a town with a river at its heart

Further, that’s where I shall go, further into the Cumbrian countryside. But I’ll begin with the year a top predator came to town. The creature is said to be secretive, if you seek diligently you might glimpse it at dawn or at dusk. This one hadn’t read the script.

The river flowed fast and the otter swam upstream, sleek and sinuous. She crunched on something crustacean, showing teeth, whiskers, dense pelt and muscular tail as she surfaced beneath our riverside walk. A photographer came each day from the Wirral and pictured her eating a fish. Her diet would be trout, bullhead or salmon, so information boards suggested. The winter the otter came to Kendal we were all eager to see, to share, to understand.

Daylight appearances and confiding behaviour were odd, but made otter watching easier. I listened to tales from the riverbank, eager to hear what this meant to others. They spoke of their relationship with the natural world. A local man lived here in boyhood, close to the river. In the 1950s, he found otter in the tributaries of the Mint and Sprint, but not in the River Kent in town. Our bitch otter was news and, during the winter of 2012-2013, she became a tourist attraction. A couple had seen her half an hour ago, opposite the Parish Church. A woman showed me otter prints in the snow below Stramongate Bridge, close to her home. A young father introduced his little girl to her first otter, and told me where he had found kingfisher as a boy. The river held us in a spectrum of time; in reminiscence, in the moment with each glimpse of otter, and here was a gift beyond price for the next generation. This is our river, our inheritance, pass it on.

Something had changed. Wildlife and people tend to lead parallel lives, but now we engaged with the life of the river in a spirit of reverence, with a respect for the natural world. Welcome, say those interpretative boards which invite us to consider the ecology of the river and to see what we can find. There was a shopping trolley and a bike in the river but otters don’t ride bikes and a river is not a rubbish dump. The idyll is rarely unalloyed but the aura around the otter suggested how things might be, if we could somehow tap into the benevolence that flowed among us.

Through Kendal, the Civic Society has plaques and offers guided walks to draw us into the story of the town. Tourists and locals like to know what’s special, what there is to see, whether it’s history or natural history, urban or rural. But the storytelling falters as we leave town and head for the countryside.

The catchment of the River Kent is an SSSI, a Site of Special Scientific Interest. So is Scout Scar, but it’s not clear what that means and acronyms don’t make a story. When we arrive in the countryside we want to know what will make our day. So what are we hoping for as we put on our boots and set forth?

Maps, photographs and all material from Cumbrian Contrasts is copyright to Jan Wiltshire

An hour after midnight twelve children made their way through the town heading for Scout Scar. They left the last of the houses behind

’there burst upon us, all unforeseen, such a ‘festival chorus’ of larks as no one of us had ever heard before. On all sides, unseen in the gray dimness, they sang as if their little hearts could hold no longer the rising flood of music, and they must needs shake it out anyhow, anywhere, with splendid unthrift, above the gray sleeping world.’ *

As the stars faded away they reached the escarpment and waited for sunrise. But lark song was the surprise and wonder of that midsummer morning in 1906.

As a naturalist, my focus is on our experience of countryside, then and now. These children give us a glimpse of how it was. 2014 saw commemorations to mark the centenary of the outbreak of The First World War, 1914-18. Throughout the year in a constant refrain, media coverage reflected on life in Britain a hundred years ago. I wrote the core of Cumbrian Contrasts in this context, with a heightened awareness of history.

Late in 2013, extensive building programmes for Kendal and Ulverston were unveiled. Change was imminent. The character of Kendal would change and so would the countryside on its doorstep.

I’d like the children of today and tomorrow to be surprised and delighted by lark song and the call of the cuckoo. I hope that may be part of their experience but both species are in dramatic decline and there’s nothing to protect the ground-nesting birds of Scout Scar. Save the skylark, that’s the watchword. The bird is an emblem of species-loss.. For wildlife and countryside everywhere we all have a part to play.

Cumbrian Contrasts celebrates the wonder of the natural world. It’s a snapshot in time, a portrait of now that reflects on the past and looks to the future.

Like those children, I walk from Kendal and head for Scout Scar. Venturing beyond, I radiate out across Cumbria excited by the prospect of all I might discover.

*Lucy M Reynolds, Sunrise on Scout Scar, from Stramongate Quaker School Magazine, September 1906.

2 Kendal: a town with a river at its heart

Further, that’s where I shall go, further into the Cumbrian countryside. But I’ll begin with the year a top predator came to town. The creature is said to be secretive, if you seek diligently you might glimpse it at dawn or at dusk. This one hadn’t read the script.

The river flowed fast and the otter swam upstream, sleek and sinuous. She crunched on something crustacean, showing teeth, whiskers, dense pelt and muscular tail as she surfaced beneath our riverside walk. A photographer came each day from the Wirral and pictured her eating a fish. Her diet would be trout, bullhead or salmon, so information boards suggested. The winter the otter came to Kendal we were all eager to see, to share, to understand.

Daylight appearances and confiding behaviour were odd, but made otter watching easier. I listened to tales from the riverbank, eager to hear what this meant to others. They spoke of their relationship with the natural world. A local man lived here in boyhood, close to the river. In the 1950s, he found otter in the tributaries of the Mint and Sprint, but not in the River Kent in town. Our bitch otter was news and, during the winter of 2012-2013, she became a tourist attraction. A couple had seen her half an hour ago, opposite the Parish Church. A woman showed me otter prints in the snow below Stramongate Bridge, close to her home. A young father introduced his little girl to her first otter, and told me where he had found kingfisher as a boy. The river held us in a spectrum of time; in reminiscence, in the moment with each glimpse of otter, and here was a gift beyond price for the next generation. This is our river, our inheritance, pass it on.

Something had changed. Wildlife and people tend to lead parallel lives, but now we engaged with the life of the river in a spirit of reverence, with a respect for the natural world. Welcome, say those interpretative boards which invite us to consider the ecology of the river and to see what we can find. There was a shopping trolley and a bike in the river but otters don’t ride bikes and a river is not a rubbish dump. The idyll is rarely unalloyed but the aura around the otter suggested how things might be, if we could somehow tap into the benevolence that flowed among us.

Through Kendal, the Civic Society has plaques and offers guided walks to draw us into the story of the town. Tourists and locals like to know what’s special, what there is to see, whether it’s history or natural history, urban or rural. But the storytelling falters as we leave town and head for the countryside.

The catchment of the River Kent is an SSSI, a Site of Special Scientific Interest. So is Scout Scar, but it’s not clear what that means and acronyms don’t make a story. When we arrive in the countryside we want to know what will make our day. So what are we hoping for as we put on our boots and set forth?

Maps, photographs and all material from Cumbrian Contrasts is copyright to Jan Wiltshire

3 Ghyll Brow an approach to Scout Scar

Where does the countryside begin? We may not find it tomorrow where we left it yesterday.

Tyre tracks slewed off the road and ploughed into the verge, demolished a pile of grit close to the mossy wall, swerved back to the road and down into town. Hardly a skid on ice in such a mild winter. Perhaps it was youths heading home after a night out, a night out of town, a night in the wilds, that transition zone where town segues into countryside. Litter along the verge told the story; cider bottles and drinks cans, fast-food wrappers and cigarettes. Aluminium cans were shoved into the earth as if they might take root and flower. Sometimes I clear up the mess, sometimes I choose to see only the rural idyll.

From the road, daphne looked darkly evergreen at the top of a steep bank against a mossy wall. This wettest of winters saw the ground saturated but to photograph those early green flowers I had to be up close. High on the bank my footing was precarious and a woman somersaulting down into the Brigsteer Road would have been a novelty. I could have summoned the mountain rescue on one of their sillier calls. Sapling spikes from a brutal flailing snagged at my legs. There were trailing brambles, blackthorn and dog rose; without gloves I couldn’t hang onto them and I slithered down the bank and landed at the feet of a woman with a black Labrador.

Those February flowers were almost hidden. ‘Honey-scented,’ writes Marjorie Blamey in her Flora.* Twice up that sodden bank was enough so I took her word for it. They were exquisite flowers to find on a winter’s morning. Through spring and summer it’s a joy to follow the sequence of flowers with something new to discover each day. Until 8 June 2015 when a maverick slashing took out the lot, two days after an item on Radio 4 reminded us that the wayside verge is a national resource, precious for its biodiversity. A careful cut in September when seed has set – that’s the schedule for this verge – but it’s not what happened.

What is this place, Ghyll Brow? At the frost line the road is at its steepest pitch and embankments hide the dramatic landscape feature of the ghyll. Sheltered and inaccessible, it is a wildlife corridor. Climb clear of the trees and the wind hits you. There’s wilder weather as you approach Scout Scar.

On many a March morning a woodpecker drummed in a sycamore over-hanging the road.

‘Can you see it?’ a passing runner called.

‘Not yet,’ I replied.

Birdsong rose from trees deep in the ghyll where bats hibernate. It’s a secret place, this ghyll whose limestone cliff plunges darkly behind the wall where spurge laurel flowers. Those snowdrops could be indigenous or thrown out from gardens, like the Spanish bluebells. Lily of the valley is native, vestigial on the verge, deep under mosses through winter.

I once saw kestrel mating here. Framed in a niche high in the barn wall, that’s where the bird always sat. One summer, a fledgling scrabbled at the wall, teetered on the mossy tiles of the barn roof. Kestrel hunting along Scout Scar escarpment was a familiar sight but numbers have dropped sharply and it’s several years since they bred here. There’s something iconic about a barn. A vernacular building, ‘ancient’ said the lady who owned it and had waited eight years uncertain of its fate. Once, the barn was a store for hay and straw for the wagon horses of timber merchants with stables on Queen Street.

Each spring, those two pastures at Ghyll Brow are white with meadow saxifrage and cuckoo flower. Too steep to plough, they’re a last stronghold of meadow saxifrage. Last June, Edward Chapman invited me to take a closer look. His farming regime suits them well and they depend upon it.

Ghyll Brow is a prelude to Scout Scar; its mood of pastoral and fresher air prepares the way for walkers, runners and cyclists as they leave the town behind. Its character was about to change.

March 2014, and down at Kendal Town Hall we gathered around plans and a map showing the barn and housing development to the north of Ghyll Brow, and south on those precious pastures. Here lies buried treasure, meadow saxifrage. ‘I found them,’ said Ivan Trimingham. So did Karen and Kevin Halcrow. So did I. Each spring we look forward to their flowering; they’ve earned their place in our hearts and we don’t want to lose them.

Not everyone feels the same. ‘It doesn’t matter to me what happens here,’ said one landowner eager to sell. ‘I’ve no children.’

Retain stone walls and trees, we scribbled our suggestions on a sheet of paper beside the map. Those mature trees festooned in ivy, dripping with mosses and ferns, a roost for bats.

‘Bats, you could kill the lot of them, for me.’

‘Rare. Is it rare?’ Lose this profusion of meadow saxifrage and it’s so much rarer.

I’m taking photographs, mapping the flora and fauna of Ghyll Brow to ensure that nothing is lost simply because no one knows it’s there. My map of buried treasure.

When Brunel was about to build the Clifton Suspension Bridge autumn squill would be destroyed. So the plant was relocated to St Vincent’s Rocks, an inaccessible spot where it thrives today. The Ghyll Brow lily of the valley could be safeguarded in this way. I’ve sent photographs and grid references to Natural England and Cumbria Wildlife Trust (and a blue sock marks the spot because the plants disappear in winter). We shall see.

*Marjorie Blamey and Christopher Grey-Wilson, The Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe, (London: Hodder and Stoughton). Meadow Saxifrage Saxifraga granulata Spurge Laurel, Daphne laureola

Where does the countryside begin? We may not find it tomorrow where we left it yesterday.

Tyre tracks slewed off the road and ploughed into the verge, demolished a pile of grit close to the mossy wall, swerved back to the road and down into town. Hardly a skid on ice in such a mild winter. Perhaps it was youths heading home after a night out, a night out of town, a night in the wilds, that transition zone where town segues into countryside. Litter along the verge told the story; cider bottles and drinks cans, fast-food wrappers and cigarettes. Aluminium cans were shoved into the earth as if they might take root and flower. Sometimes I clear up the mess, sometimes I choose to see only the rural idyll.

From the road, daphne looked darkly evergreen at the top of a steep bank against a mossy wall. This wettest of winters saw the ground saturated but to photograph those early green flowers I had to be up close. High on the bank my footing was precarious and a woman somersaulting down into the Brigsteer Road would have been a novelty. I could have summoned the mountain rescue on one of their sillier calls. Sapling spikes from a brutal flailing snagged at my legs. There were trailing brambles, blackthorn and dog rose; without gloves I couldn’t hang onto them and I slithered down the bank and landed at the feet of a woman with a black Labrador.

Those February flowers were almost hidden. ‘Honey-scented,’ writes Marjorie Blamey in her Flora.* Twice up that sodden bank was enough so I took her word for it. They were exquisite flowers to find on a winter’s morning. Through spring and summer it’s a joy to follow the sequence of flowers with something new to discover each day. Until 8 June 2015 when a maverick slashing took out the lot, two days after an item on Radio 4 reminded us that the wayside verge is a national resource, precious for its biodiversity. A careful cut in September when seed has set – that’s the schedule for this verge – but it’s not what happened.

What is this place, Ghyll Brow? At the frost line the road is at its steepest pitch and embankments hide the dramatic landscape feature of the ghyll. Sheltered and inaccessible, it is a wildlife corridor. Climb clear of the trees and the wind hits you. There’s wilder weather as you approach Scout Scar.

On many a March morning a woodpecker drummed in a sycamore over-hanging the road.

‘Can you see it?’ a passing runner called.

‘Not yet,’ I replied.

Birdsong rose from trees deep in the ghyll where bats hibernate. It’s a secret place, this ghyll whose limestone cliff plunges darkly behind the wall where spurge laurel flowers. Those snowdrops could be indigenous or thrown out from gardens, like the Spanish bluebells. Lily of the valley is native, vestigial on the verge, deep under mosses through winter.

I once saw kestrel mating here. Framed in a niche high in the barn wall, that’s where the bird always sat. One summer, a fledgling scrabbled at the wall, teetered on the mossy tiles of the barn roof. Kestrel hunting along Scout Scar escarpment was a familiar sight but numbers have dropped sharply and it’s several years since they bred here. There’s something iconic about a barn. A vernacular building, ‘ancient’ said the lady who owned it and had waited eight years uncertain of its fate. Once, the barn was a store for hay and straw for the wagon horses of timber merchants with stables on Queen Street.

Each spring, those two pastures at Ghyll Brow are white with meadow saxifrage and cuckoo flower. Too steep to plough, they’re a last stronghold of meadow saxifrage. Last June, Edward Chapman invited me to take a closer look. His farming regime suits them well and they depend upon it.

Ghyll Brow is a prelude to Scout Scar; its mood of pastoral and fresher air prepares the way for walkers, runners and cyclists as they leave the town behind. Its character was about to change.

March 2014, and down at Kendal Town Hall we gathered around plans and a map showing the barn and housing development to the north of Ghyll Brow, and south on those precious pastures. Here lies buried treasure, meadow saxifrage. ‘I found them,’ said Ivan Trimingham. So did Karen and Kevin Halcrow. So did I. Each spring we look forward to their flowering; they’ve earned their place in our hearts and we don’t want to lose them.

Not everyone feels the same. ‘It doesn’t matter to me what happens here,’ said one landowner eager to sell. ‘I’ve no children.’

Retain stone walls and trees, we scribbled our suggestions on a sheet of paper beside the map. Those mature trees festooned in ivy, dripping with mosses and ferns, a roost for bats.

‘Bats, you could kill the lot of them, for me.’

‘Rare. Is it rare?’ Lose this profusion of meadow saxifrage and it’s so much rarer.

I’m taking photographs, mapping the flora and fauna of Ghyll Brow to ensure that nothing is lost simply because no one knows it’s there. My map of buried treasure.

When Brunel was about to build the Clifton Suspension Bridge autumn squill would be destroyed. So the plant was relocated to St Vincent’s Rocks, an inaccessible spot where it thrives today. The Ghyll Brow lily of the valley could be safeguarded in this way. I’ve sent photographs and grid references to Natural England and Cumbria Wildlife Trust (and a blue sock marks the spot because the plants disappear in winter). We shall see.

*Marjorie Blamey and Christopher Grey-Wilson, The Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe, (London: Hodder and Stoughton). Meadow Saxifrage Saxifraga granulata Spurge Laurel, Daphne laureola