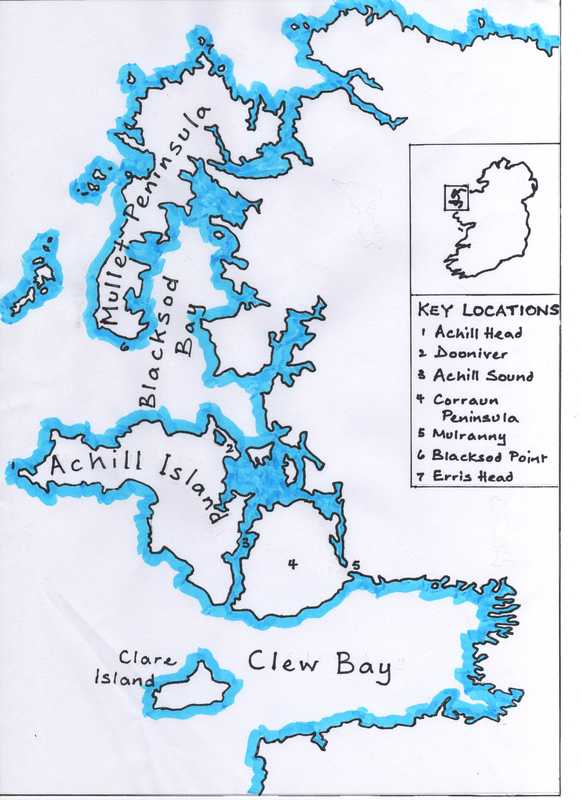

Atlantic Odyssey was inspired by an exploration of Achill Island and the Armada Coast of County Mayo, Ireland. History and natural history meet here. Achill Island was a new venture in 2013 but we have often visited the west coast of Ireland and the Armada Odyssey has long held a fascination for me. A hand-drawn map accompanies this short on-line book.

Atlantic Odyssey

By Jan Wiltshire

|

Full fathom five thy father lies

Of his bones are coral made Those are pearls that were his eyes Nothing of him that doth fade But doth suffer a sea-change Into something rich and strange Song for Ferdinand, shipwrecked on Prospero’s isle in the storm he raised. Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Walking beside the Atlantic Ocean, I looked down at my feet to find coral. Beautiful and strange! The coral strand of Mannin Bay, Connemara. Years ago, it was. |

To Achill Island, County Mayo

The west coast of Ireland can be wet and windy any time, any season. This is Atlantic coast, warmed by the strong current of the Gulf Stream, the North Atlantic Drift, without whose influence the climate at these latitudes would be very different.

With a trip to Achill Island, County Mayo, in June 2013, this was a new part of Ireland to explore. I was preoccupied by Atlantic weather systems, the Armada of 1588, and their interaction. Here was an opportunity to reprise the shipwreck coast. If there were fog, wind and rain that would be mood-music for the sequence of severe storms that caused havoc during September 1588. The coast-road around Achill Island was signed Atlantic Drive, Armada Drive, and these themes took hold.

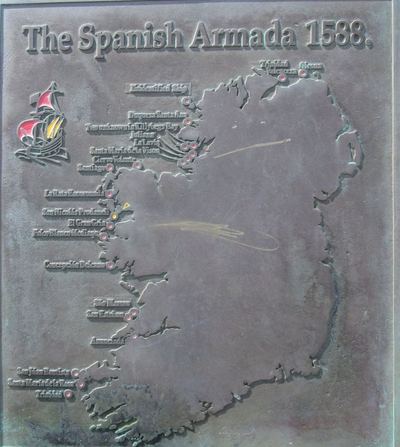

Weather can drive story, change its direction, and outcome. The invasion of England was the Armada grand design, and battle in the English Channel was expected. And inconclusive. King Philip's fleet was helpless against the power of storms that drove his Armada into the North Sea, around the North and West of Scotland, the Orkneys, scattering and wrecking along the west coast of Ireland. A voyage into the unknown: terra incognita, mare incognitum. Spain at the height of her imperial power, brought low by Atlantic storms. Who can fight against the weather, asked King Philip? Here was hubris. And an archetypal story: after the battle, the disastrous journey home.

March 2013 had been exceptionally cold, a long winter and the grass had not begun to grow until the end of May. That first Sunday in June was wet and cold. For three days and nights the pull of the tide clattered the stones in the bay, presaging change. Then came high pressure and exceptional weather. Ireland had seen nothing like it for fifty years. These were rare days.

The heat wave influenced the choices we made, shifted the emphasis. There were mountains and coastal paths, but secluded beaches were a delight and our focus grew littoral. Here the air was cool and the water refreshing, so we lingered. I might have dipped a toe in the Atlantic Ocean, paddling perhaps, but it had always been too cool, too wet and windy for more. Now was the time to swim, to explore, and the story began to unfold in unexpected ways.

ACHILL SOUND

Equipped with maps, we begin to explore Achill Island.

A sunny day, with the sweet smell of burning turf in the warm air. Sea-mist hangs about the shore and luminous white cloud caps the tops. Listening to cuckoo and whitethroat, we sit overlooking Achill Sound which links Blacksod Bay to the north with Clew Bay to the south. Even on a calm day current and tidal race make the Sound treacherous, and in winter it can be like a cauldron. Commanding Achill Sound, discreet but dominant, Kildavnet was one of a nexus of O’Malley castles. The clan had dominion here during the 16th century and the formidable Granuaile O’Malley made sure they kept it. Out in the Atlantic, sailing ships unfamiliar with this coast and seeking landfall would do well to secure O’Malley pilots skilled in the complex and treacherous currents of inshore waters, inlets and creeks.

At the most southerly point of Achill Island we climb Carrowgarve, up into blanket bog with dwarf alpine willow and St Patrick’s cabbage flowering in niches of rock. Across on the Corraun Peninsula, there are lazy beds and ruined cottages and to the south, Clare Island. Going down to Achill Sound, we walk through iris coming into flower, their yellow petals flecked with tiny black flies.

We take the Atlantic Drive around the tip of Achill Island, to the wild and rugged west coast. High cliffs and sea-stacks, creation of Atlantic storms, exposed to the full force of the waves. In a blue sky, high cirrus and cumulus cloud mirror patterns of spin-drift on the blue of the ocean.

Sitting on the cliff-top on a tranquil day in spring, we contemplate this shipwreck coast. The Atlantic roar reminds us Poseidon rules, the ill-tempered Sea God intent on wrecking Odysseus on his voyage home. Land is in sight, but look at those jagged rocks, think of the hidden reefs! The day is calm, but if Odysseus’ men untie the bag of winds and unleash their fury they’ll be blown off-course, back out to sea and who knows where. The nightmare voyage goes on and on, pitched between hope and despair. There can be no chart. Some ships will simply vanish, their story lost. For all time, this is shipwreck coast.

A steep descent along the Atlantic Drive, bordered with large white stones- beware, high cliffs!

ACHILL HEAD.

The allure of the Atlantic draws us to Benmore and Achill Head until we can go no further west, so we sit on the cliff-top in the sun, looking out along the spine of the exposed headland tapering into the Ocean. Beautiful, wild and inaccessible.

A Mountain Blackface ewe and lamb nibble the short turf of the headland, but the cliff face is out of reach and heather grows thick and luxuriant. Heather and a secret maritime flora we cannot tell. An insistent alarm call warns us we have strayed into someone else’s territory. Intruders are not welcome on the stonechats‘ remote headland, and our delight in them is not reciprocated. Dancing in display flight, he flutters against the blue and hovers above us. And down he comes, to his outlying rock poised between land and ocean, pictured against the deep blue sea, guarding his mate. How handsome he is, and what a perfect nest site they have chosen- a maritime rock-garden softened with pale green lichens and dark red sedum.

In the col below, a stream runs through lochans down into the bay and along its banks are stone structures, like sheep folds. But seventeen of them? In summers past, people brought their herds to the headland to graze fresh pastures, living in simple stone huts strung out along the stream. Booley houses they are called, a summer of booleying, milking their cattle. The screes of Croaghaun rise above the col and high cliffs fall a sheer 2000 feet into an ocean that can rarely be so serene. A flight of gannet rounds the headland, brilliant white in the strong sunlight. In home waters, a fisherman checks his lobster pots, skilled in reef currents and tidal races, down among the rarities of the reef communities, sponges and brachiopods , outlandish creatures. Those steep, sublittoral reefs below Croaghaun are hidden from view in a marine habitat beautiful and strange.

For sailing ships forced to seek landfall in shallow bays and inlets, this coastline is fraught with danger. Imagine a sequence of severe storms and squalls, no sea-charts, location unknown, and looming through the fog the cliffs of Croaghaun, amongst the highest in Europe. World class seamanship so cruelly tested, over and over. Bewilderment and confusion, that’s the Armada story on their Atlantic Odyssey. Those figures watching from the headland could be malevolent. Alliances do not hold and a tradition of plunder follows in the wake of shipwreck. Men are weighed down and drowned by gold sewn into their garments, or set upon by watchers on the shore. Storm upon storm during September 1588, and day after day Armada ships founder all along the west coast.

In spring and autumn, Atlantic storms with sustained westerlies can disrupt migration patterns. Disorientated, separated from the flock, birds seek landfall on off-shore islands and headlands, promontories like Achill Head, the most westerly point of Achill Island. Way off course, hopelessly lost, exhausted vagrants seek food and shelter. Creatures of the storm.

The west coast of Ireland can be wet and windy any time, any season. This is Atlantic coast, warmed by the strong current of the Gulf Stream, the North Atlantic Drift, without whose influence the climate at these latitudes would be very different.

With a trip to Achill Island, County Mayo, in June 2013, this was a new part of Ireland to explore. I was preoccupied by Atlantic weather systems, the Armada of 1588, and their interaction. Here was an opportunity to reprise the shipwreck coast. If there were fog, wind and rain that would be mood-music for the sequence of severe storms that caused havoc during September 1588. The coast-road around Achill Island was signed Atlantic Drive, Armada Drive, and these themes took hold.

Weather can drive story, change its direction, and outcome. The invasion of England was the Armada grand design, and battle in the English Channel was expected. And inconclusive. King Philip's fleet was helpless against the power of storms that drove his Armada into the North Sea, around the North and West of Scotland, the Orkneys, scattering and wrecking along the west coast of Ireland. A voyage into the unknown: terra incognita, mare incognitum. Spain at the height of her imperial power, brought low by Atlantic storms. Who can fight against the weather, asked King Philip? Here was hubris. And an archetypal story: after the battle, the disastrous journey home.

March 2013 had been exceptionally cold, a long winter and the grass had not begun to grow until the end of May. That first Sunday in June was wet and cold. For three days and nights the pull of the tide clattered the stones in the bay, presaging change. Then came high pressure and exceptional weather. Ireland had seen nothing like it for fifty years. These were rare days.

The heat wave influenced the choices we made, shifted the emphasis. There were mountains and coastal paths, but secluded beaches were a delight and our focus grew littoral. Here the air was cool and the water refreshing, so we lingered. I might have dipped a toe in the Atlantic Ocean, paddling perhaps, but it had always been too cool, too wet and windy for more. Now was the time to swim, to explore, and the story began to unfold in unexpected ways.

ACHILL SOUND

Equipped with maps, we begin to explore Achill Island.

A sunny day, with the sweet smell of burning turf in the warm air. Sea-mist hangs about the shore and luminous white cloud caps the tops. Listening to cuckoo and whitethroat, we sit overlooking Achill Sound which links Blacksod Bay to the north with Clew Bay to the south. Even on a calm day current and tidal race make the Sound treacherous, and in winter it can be like a cauldron. Commanding Achill Sound, discreet but dominant, Kildavnet was one of a nexus of O’Malley castles. The clan had dominion here during the 16th century and the formidable Granuaile O’Malley made sure they kept it. Out in the Atlantic, sailing ships unfamiliar with this coast and seeking landfall would do well to secure O’Malley pilots skilled in the complex and treacherous currents of inshore waters, inlets and creeks.

At the most southerly point of Achill Island we climb Carrowgarve, up into blanket bog with dwarf alpine willow and St Patrick’s cabbage flowering in niches of rock. Across on the Corraun Peninsula, there are lazy beds and ruined cottages and to the south, Clare Island. Going down to Achill Sound, we walk through iris coming into flower, their yellow petals flecked with tiny black flies.

We take the Atlantic Drive around the tip of Achill Island, to the wild and rugged west coast. High cliffs and sea-stacks, creation of Atlantic storms, exposed to the full force of the waves. In a blue sky, high cirrus and cumulus cloud mirror patterns of spin-drift on the blue of the ocean.

Sitting on the cliff-top on a tranquil day in spring, we contemplate this shipwreck coast. The Atlantic roar reminds us Poseidon rules, the ill-tempered Sea God intent on wrecking Odysseus on his voyage home. Land is in sight, but look at those jagged rocks, think of the hidden reefs! The day is calm, but if Odysseus’ men untie the bag of winds and unleash their fury they’ll be blown off-course, back out to sea and who knows where. The nightmare voyage goes on and on, pitched between hope and despair. There can be no chart. Some ships will simply vanish, their story lost. For all time, this is shipwreck coast.

A steep descent along the Atlantic Drive, bordered with large white stones- beware, high cliffs!

ACHILL HEAD.

The allure of the Atlantic draws us to Benmore and Achill Head until we can go no further west, so we sit on the cliff-top in the sun, looking out along the spine of the exposed headland tapering into the Ocean. Beautiful, wild and inaccessible.

A Mountain Blackface ewe and lamb nibble the short turf of the headland, but the cliff face is out of reach and heather grows thick and luxuriant. Heather and a secret maritime flora we cannot tell. An insistent alarm call warns us we have strayed into someone else’s territory. Intruders are not welcome on the stonechats‘ remote headland, and our delight in them is not reciprocated. Dancing in display flight, he flutters against the blue and hovers above us. And down he comes, to his outlying rock poised between land and ocean, pictured against the deep blue sea, guarding his mate. How handsome he is, and what a perfect nest site they have chosen- a maritime rock-garden softened with pale green lichens and dark red sedum.

In the col below, a stream runs through lochans down into the bay and along its banks are stone structures, like sheep folds. But seventeen of them? In summers past, people brought their herds to the headland to graze fresh pastures, living in simple stone huts strung out along the stream. Booley houses they are called, a summer of booleying, milking their cattle. The screes of Croaghaun rise above the col and high cliffs fall a sheer 2000 feet into an ocean that can rarely be so serene. A flight of gannet rounds the headland, brilliant white in the strong sunlight. In home waters, a fisherman checks his lobster pots, skilled in reef currents and tidal races, down among the rarities of the reef communities, sponges and brachiopods , outlandish creatures. Those steep, sublittoral reefs below Croaghaun are hidden from view in a marine habitat beautiful and strange.

For sailing ships forced to seek landfall in shallow bays and inlets, this coastline is fraught with danger. Imagine a sequence of severe storms and squalls, no sea-charts, location unknown, and looming through the fog the cliffs of Croaghaun, amongst the highest in Europe. World class seamanship so cruelly tested, over and over. Bewilderment and confusion, that’s the Armada story on their Atlantic Odyssey. Those figures watching from the headland could be malevolent. Alliances do not hold and a tradition of plunder follows in the wake of shipwreck. Men are weighed down and drowned by gold sewn into their garments, or set upon by watchers on the shore. Storm upon storm during September 1588, and day after day Armada ships founder all along the west coast.

In spring and autumn, Atlantic storms with sustained westerlies can disrupt migration patterns. Disorientated, separated from the flock, birds seek landfall on off-shore islands and headlands, promontories like Achill Head, the most westerly point of Achill Island. Way off course, hopelessly lost, exhausted vagrants seek food and shelter. Creatures of the storm.

Blacksod Bay: Bull’s Mouth and Dooniver Strand

Blacksod Bay, the name sounds forbidding. Exceptional rainfall is the prerequisite for blanket bog that can appear desolate, from a distance. In close-up, its flora is intricate and beautiful and I love it. Amongst hare’s-tail cotton grass lie fossilised trees dug out of the turf, exhumed from deep history, from Neolithic times when the coast was thickly wooded. Turf is stacked and drying above the deep-cut peat slab, the black sod.

On the approach to Dooniver Strand, peace and tranquillity reign and when calves with sun-gold earrings step into the road and halt before us we yield, and are drawn deep into the aura of the morning. Hyperion’s herd, Cattle of the Sun God as their ear-tags tell. We go down to the lough and watch them amble down to the shore. Slievemore reflects in the still water, the mountain is a presence on the island. The only sound is a sloshing of water as a black cow scratches itself on the bank and wades toward the group. The Sun God rose early and shines benevolent on his precious cattle, herd book and passports safe in his chariot. All is well. Hyperion will play his part, as long as we play ours. An outrage from Odysseus’ men could wreck the whole heavenly harmony and, for good and ill, we are all Odysseus’ men.

We are heading for Bull’s Mouth! A shuddering prospect, that constricted channel between Dooniver Point and Inishbiggle out in Achill Sound! In winter, strong currents and rough seas can make the island inaccessible. Today, the bull is dozing. In summer, the O’Malley would relish a spell of weather like this to take their cattle into the mountains for fresh grazing, going booleying. Their wealth was cattle and with herds to protect and in-fighting amongst the clans it was never a quiet life. The stories they had to tell, of cattle raids on land and piracy at sea!

The sea is never far away on this indented coastline and everywhere skylark sing, claiming the furthest flung outposts where fingers of land reach into the ocean. Pastures of bullrush, ditches of spearwort and ragged robin, as freshwater mingles with salt where sea campion and sea pink run down to Dooniver Strand.

Vistas from Dooniver Strand on a perfect day! Aquamarine, a dissolve of colour, glossy wet sand running into the waters of the bay, sea-weeds anchored in rock and floated by the tide, the blue of the sky and a ripple of bright cloud all reflected in the calm bay to compose aquamarine, the waters of the ocean. Through the stillness and silence comes the sound of distant laughter where a couple play in the water with their child, far off, far out in the shallow waters of the bay. Time dissolves in tinctures of aquamarine. Out on a reef, a shag presides. Swans fly above us and we hear their wing-beats. Reflections, and strong shadows. Solitude.

Later, who knows when, we walk into cool air and into the water, and gasp in surprise to find it warm. Through the gentlest waves, patterns of sunlight refract on rippled sand. On and on through clear water, to rocks where mystery fish dart in and out of seaweed. Translucent fish, a glimpse, no more. Four little fish swim about our ankles nibbling our feet- if we do not imagine it. We venture into an unknown zone where conjecture rules. Dark strands flicker through the water. Shoals of innumerable tiny fish, we have no idea what they might be so we call them sea-grass. It’s something in the way they move, the sway of the shoal.

In the extreme conditions of the upper shore, barnacle, limpet, and dog whelk adhere to exposed rock, a crust of shells immobilised. The rock pool is a refuge as the tide retreats but, under the relentless sun, water evaporates and salinity increases, smears of algal slime glisten and crisp, rank seaweeds look fagged and desiccated. Life is fine-tuned to the rhythm of the tide. Creatures of rock and rock pool sense the tide is turning, their tidal- clocks tell them so. The first refreshing waves splash onto rock, and the rising tide begins to rehydrate lank filaments of bright green Ulva that float out from rock holdfasts as the seaweed shallows revive. On the last of the sand our footsteps pop the pods of bladderwrack, Fucus vesiculosus.

A heron stands in the shallows, intent on fish. The in-coming tide liberates the creatures of the inter-tidal zone to breed, to wander in search of food, to eat each other. Survival strategies and integrated weapons- systems to the fore! Predator and prey confront each other in arms and armour physical and chemical evolved and adapted over hundreds of millions of years. Their time-scale redefines epic.

Concealment . The predatory cuttle fish lurks, and colour-change confuses an enemy in its ruse of hide and seek. Hermit crabs seek discarded shells, the best fit and a colour that will blend into the background. Crypsis is an effective defence.

An exoskeleton is armour. The crab carapace protects its soft body from attack, each jointed limb encased in shell.

To defend itself against the pounding of Atlantic waves, the limpet hunkers down in a shallow depression in the rock, its home scar. The mollusc feeds using its toothed radula to scrape algae off the rock, to smooth the home scar into a tight fit. Rasping wears down the rows of teeth so the radula is constantly renewed. Sensory tentacles emerge from beneath the rim of the limpet’s conical shell as it detects a marauding starfish with spiny exoskeleton. A probing starfish arm tries to prise it from the rock and the limpet tilts in defence, grinding the serrated edge of its shell back and forth to damage the starfish tube feet that grasp with suction cups and adhere to prey.

The dog whelk predates cold water barnacles and mussels: mollusc on mollusc. Assaulting the mussel bed, the dog whelk drills through shell with its modified radula, secreting a shell-dissolving chemical, paralysing its prey, with digestive enzymes to liquefy the soft flesh and suck it out. Sensing attack, the mussel colony secretes adhesive threads to snare the dog whelk. If mussels can tether it to the rock the whelk will starve.

It’s internecine warfare for the beadlet anemone, Actinia equina. Around its feeding tentacles it has an outer ring of blue beadlets, fighting tentacles equipped with stinging cells, firing venomous darts in the battle for food and territory.

The soft-bodied lemon sea slug protects itself by absorbing toxins from the sponges it preys upon.

Armada guns, long silenced, lie encrusted on the ocean bed. In a sea change rich and strange, life pulses through shipwreck. Fish dart through fans and fronds of seaweeds, through soft corals, sponges, and colonies of crustaceans. Here are niche habitats and nurseries of marine creatures amidst the unending battle for survival.

The Corraun Peninsula, Clew Bay, and Clare Island

At Mulranny, the estuary of the Murrevagh River becomes a network of soupy channels meandering through Atlantic salt marsh. Seen from above it looks unremarkable. Come closer, for a burst of floral colour. All across the salt marsh there are drifts of sea pink, thrift, Armeria maritima. And Blackface sheep graze in the thick of the flowers. ‘Don’t fall in!’ Stepping back from an overhang of thrift and peering into liquid mud, I’m struck by all that we are not seeing: mud snails, organisms that oxygenate these mud channels, the bio-chemistry of the estuary. Here is natural equilibrium, a habitat to absorb the force of winds and waves, Nature’s flood control.

We walk the harbour pier, looking amongst the rocks and seaweed for otter and harbour seals. We might fish for Atlantic salmon and sea trout- when the season is right, if we were fishermen. The ocean is so calm that voices carry far across the water from youngsters on a boat.

Jackdaws caw from the battlements of Rockfleet Castle, strategically situated on an inlet of Clew Bay. On Clare Island, a third O’Malley stronghold dominates the mouth of the bay. The O’Malley: terra marique potens, powerful on land and sea. Granuaile O’Malley asserted her power in 1577 by offering three galleys and two hundred fighting men to Sir Henry Sidney, Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Deputy in Ireland. When Armada vessels sought shelter in Clew Bay the O’Malley alliance proved equivocal.

Clew Bay with its host of drowned drumlins, so many islands. A bay with shallow straits, deep channels and strong tidal currents so unpredictable a ship out in the Atlantic would need an O’Malley pilot to guide it to safe anchorage. In the great storm of 21st September 1588, El Gran Grin ran aground off Clare Island and many men were drowned. Of their bones are coral made. Here, right here amongst the drowned drumlins, shipwreck and coral meet. Wave power washes out a coarse gravel of chalky nodules from beds of maerl, a coralline red algae, a calcified seaweed. Like crushed coral, chalky skeletons, brittle branches accumulate in maerl beds for a thousand years. Nearest the light, a purple-pink layer of living maerl grows infinitely slowly, producing oxygen through photosynthesis. Red algae, Rhodophyta. Life-giving maerl beds, a nursery for algae and marine creatures. But it’s a fragile habitat and climate change could disrupt the Rhodophyta.

Skylark are singing as we stop along the Armada Drive to study a map of shipwreck sites, El Gran Grin and San Nicolas Prodaneli wrecked here. A repeated alarm call from the pipit of the place tells us to clear off. Enough of reading information boards! Right now she has young to feed and a beak-full of insect wings and legs to deliver. The imperative of now! Who cares about 1588?

Down to the beach and into the Atlantic Ocean where sunlight refracts through clear, shallow water in coruscating patterns. Starbursts on the sea bed. A mingling of light and shadows. Clusters of shadows float to and fro on rippling waves. What creature makes this drift of shadows? How can there be shadows without substance? Awash on the waves and all about our feet there are transparencies of palest pink. Dirigibles, silk parachutes dragging their shadows. Do they sting, these delicate creatures? With red combs about their amorphous, dilating shapes, are they comb-jellyfish? Once again there are shoals of sea-grass, thousands of tiny fish darting in and out of seaweed rocks. Bizarre and beautiful marine creatures drifting and swimming in the shallows.

Pink parachutes and sea-grass: what a mystery! After the magic, the science, the need to know. It will come, it always does. Travelling light, we had no field guides for the intertidal zones and marine biology, no internet connection. But when we encountered pink parachutes at Clew Bay I ran to fetch my camera. We watched the erratic pulse of waves about the rocks to frame the swimming creatures before they were washed away. Grains of sand showed through the silk of diaphanous parachutes. Shoot the shadows, that was the trick. I brought home a single image of sea-grass. Without it, I could not have made the connection and understood the story unfolding unseen and right before our eyes. A story of loss, and epic as climate change. It is the undertow for our times, and inescapable.

Erris Head and Blacksod Point. The Mullet Peninsula (Barony of Erris).

La Santa Maria Encoronada ran aground at Blacksod Bay. Don Alonso de Leiva fired his ship, marched north, then down the Mullet Peninsula where he knew the Duquesa Santa Ana was undergoing repairs. With an overload of shipwrecked soldiers and mariners on a patched-up vessel they prepared to resume their voyage.

Leaving Achill Island, we follow in his footsteps, travelling around Blacksod Bay and down to the southern tip of the Mullet Peninsula where we plan to overnight. A remote and desolate look-out point to scan the entrance to the bay and involve us in the action, that’s the objective. Remote and desolate is liminal, a threshold into the past, that’s where we’ll come closest to Don Alonso and his men who will have struggled through blanket bog, carrying all they might salvage. How could Erris feed an army, an influx of half-starved vagrants descending like flocks of migrating geese who strip the good grazing and risk the farmers’ wrath?

Hunger stalks Odysseus and his men. Making landfall, they see sleek and healthy flocks on a headland. Bringing havoc to pastoral, they help themselves to cheese, whey and meat stored in a nomadic shepherd’s cave. And Poseidon the Sea God rages to see his son Cyclops blinded, his flocks stolen and driven onto Odysseus’ ships. The Sea God’s anger festers. When the time comes he will avenge his son in elemental fury.

The Mullet Peninsula is low-lying, with mountain vistas. At the north-westerly tip of the peninsula, Erris Head is a place of very high rainfall. We walk an earth-bank, once the parish boundary, toward headland and exposed cliffs where fulmar nest. Thrift and bird’s-foot trefoil at our feet, and a ditch of bright green sphagnum moss. Chough in a geo and gannet out at sea. Underlying its peace and solitude, there’s a welcome in this well-designed walk. Erris is cattle country, lush and fertile. A hospitable farmer, come to feed his black-face ewes and lambs, invites us to camp on his land.

With the landmark of Erris Head in sight, storms on 21st September 1588 drove three merchantmen of the Levant squadron into Donegal Bay where they anchored off-shore until the next great storm drove them onto rocks where they broke to pieces. Captain Francisco de Cuellar could not swim. From the poop of the Lavia, he watched men drowning and saw those who reached the beach set upon by ‘savages’ and stripped naked for the gold coins sewn into their garments. After the storm, the tide cast the bodies of the drowned onto the sands.

The creation of Atlantic storms, the west coast of the Mullet Peninsula is strewn with uninhabited islands, rocks and shoals. We drive west along a track, rocking and rolling through potholes and ruts, bound for the ocean hidden beyond sand dunes thick with marram grass. Skylark sing over machair scattered with daisies and birds foot trefoil. We step clear of sheltering dunes and a blindfold is whisked away to reveal a secluded Atlantic beach with foaming waves beneath a fine sky. Rock pools with crabs and beadlet anemones surround rocks crusted with barnacles and blue-black mussels. We sit on cobbles hurled ashore by Atlantic storms, heaved high up the beach. The peace of the place!

Blacksod Bay, the name sounds forbidding. Exceptional rainfall is the prerequisite for blanket bog that can appear desolate, from a distance. In close-up, its flora is intricate and beautiful and I love it. Amongst hare’s-tail cotton grass lie fossilised trees dug out of the turf, exhumed from deep history, from Neolithic times when the coast was thickly wooded. Turf is stacked and drying above the deep-cut peat slab, the black sod.

On the approach to Dooniver Strand, peace and tranquillity reign and when calves with sun-gold earrings step into the road and halt before us we yield, and are drawn deep into the aura of the morning. Hyperion’s herd, Cattle of the Sun God as their ear-tags tell. We go down to the lough and watch them amble down to the shore. Slievemore reflects in the still water, the mountain is a presence on the island. The only sound is a sloshing of water as a black cow scratches itself on the bank and wades toward the group. The Sun God rose early and shines benevolent on his precious cattle, herd book and passports safe in his chariot. All is well. Hyperion will play his part, as long as we play ours. An outrage from Odysseus’ men could wreck the whole heavenly harmony and, for good and ill, we are all Odysseus’ men.

We are heading for Bull’s Mouth! A shuddering prospect, that constricted channel between Dooniver Point and Inishbiggle out in Achill Sound! In winter, strong currents and rough seas can make the island inaccessible. Today, the bull is dozing. In summer, the O’Malley would relish a spell of weather like this to take their cattle into the mountains for fresh grazing, going booleying. Their wealth was cattle and with herds to protect and in-fighting amongst the clans it was never a quiet life. The stories they had to tell, of cattle raids on land and piracy at sea!

The sea is never far away on this indented coastline and everywhere skylark sing, claiming the furthest flung outposts where fingers of land reach into the ocean. Pastures of bullrush, ditches of spearwort and ragged robin, as freshwater mingles with salt where sea campion and sea pink run down to Dooniver Strand.

Vistas from Dooniver Strand on a perfect day! Aquamarine, a dissolve of colour, glossy wet sand running into the waters of the bay, sea-weeds anchored in rock and floated by the tide, the blue of the sky and a ripple of bright cloud all reflected in the calm bay to compose aquamarine, the waters of the ocean. Through the stillness and silence comes the sound of distant laughter where a couple play in the water with their child, far off, far out in the shallow waters of the bay. Time dissolves in tinctures of aquamarine. Out on a reef, a shag presides. Swans fly above us and we hear their wing-beats. Reflections, and strong shadows. Solitude.

Later, who knows when, we walk into cool air and into the water, and gasp in surprise to find it warm. Through the gentlest waves, patterns of sunlight refract on rippled sand. On and on through clear water, to rocks where mystery fish dart in and out of seaweed. Translucent fish, a glimpse, no more. Four little fish swim about our ankles nibbling our feet- if we do not imagine it. We venture into an unknown zone where conjecture rules. Dark strands flicker through the water. Shoals of innumerable tiny fish, we have no idea what they might be so we call them sea-grass. It’s something in the way they move, the sway of the shoal.

In the extreme conditions of the upper shore, barnacle, limpet, and dog whelk adhere to exposed rock, a crust of shells immobilised. The rock pool is a refuge as the tide retreats but, under the relentless sun, water evaporates and salinity increases, smears of algal slime glisten and crisp, rank seaweeds look fagged and desiccated. Life is fine-tuned to the rhythm of the tide. Creatures of rock and rock pool sense the tide is turning, their tidal- clocks tell them so. The first refreshing waves splash onto rock, and the rising tide begins to rehydrate lank filaments of bright green Ulva that float out from rock holdfasts as the seaweed shallows revive. On the last of the sand our footsteps pop the pods of bladderwrack, Fucus vesiculosus.

A heron stands in the shallows, intent on fish. The in-coming tide liberates the creatures of the inter-tidal zone to breed, to wander in search of food, to eat each other. Survival strategies and integrated weapons- systems to the fore! Predator and prey confront each other in arms and armour physical and chemical evolved and adapted over hundreds of millions of years. Their time-scale redefines epic.

Concealment . The predatory cuttle fish lurks, and colour-change confuses an enemy in its ruse of hide and seek. Hermit crabs seek discarded shells, the best fit and a colour that will blend into the background. Crypsis is an effective defence.

An exoskeleton is armour. The crab carapace protects its soft body from attack, each jointed limb encased in shell.

To defend itself against the pounding of Atlantic waves, the limpet hunkers down in a shallow depression in the rock, its home scar. The mollusc feeds using its toothed radula to scrape algae off the rock, to smooth the home scar into a tight fit. Rasping wears down the rows of teeth so the radula is constantly renewed. Sensory tentacles emerge from beneath the rim of the limpet’s conical shell as it detects a marauding starfish with spiny exoskeleton. A probing starfish arm tries to prise it from the rock and the limpet tilts in defence, grinding the serrated edge of its shell back and forth to damage the starfish tube feet that grasp with suction cups and adhere to prey.

The dog whelk predates cold water barnacles and mussels: mollusc on mollusc. Assaulting the mussel bed, the dog whelk drills through shell with its modified radula, secreting a shell-dissolving chemical, paralysing its prey, with digestive enzymes to liquefy the soft flesh and suck it out. Sensing attack, the mussel colony secretes adhesive threads to snare the dog whelk. If mussels can tether it to the rock the whelk will starve.

It’s internecine warfare for the beadlet anemone, Actinia equina. Around its feeding tentacles it has an outer ring of blue beadlets, fighting tentacles equipped with stinging cells, firing venomous darts in the battle for food and territory.

The soft-bodied lemon sea slug protects itself by absorbing toxins from the sponges it preys upon.

Armada guns, long silenced, lie encrusted on the ocean bed. In a sea change rich and strange, life pulses through shipwreck. Fish dart through fans and fronds of seaweeds, through soft corals, sponges, and colonies of crustaceans. Here are niche habitats and nurseries of marine creatures amidst the unending battle for survival.

The Corraun Peninsula, Clew Bay, and Clare Island

At Mulranny, the estuary of the Murrevagh River becomes a network of soupy channels meandering through Atlantic salt marsh. Seen from above it looks unremarkable. Come closer, for a burst of floral colour. All across the salt marsh there are drifts of sea pink, thrift, Armeria maritima. And Blackface sheep graze in the thick of the flowers. ‘Don’t fall in!’ Stepping back from an overhang of thrift and peering into liquid mud, I’m struck by all that we are not seeing: mud snails, organisms that oxygenate these mud channels, the bio-chemistry of the estuary. Here is natural equilibrium, a habitat to absorb the force of winds and waves, Nature’s flood control.

We walk the harbour pier, looking amongst the rocks and seaweed for otter and harbour seals. We might fish for Atlantic salmon and sea trout- when the season is right, if we were fishermen. The ocean is so calm that voices carry far across the water from youngsters on a boat.

Jackdaws caw from the battlements of Rockfleet Castle, strategically situated on an inlet of Clew Bay. On Clare Island, a third O’Malley stronghold dominates the mouth of the bay. The O’Malley: terra marique potens, powerful on land and sea. Granuaile O’Malley asserted her power in 1577 by offering three galleys and two hundred fighting men to Sir Henry Sidney, Queen Elizabeth’s Lord Deputy in Ireland. When Armada vessels sought shelter in Clew Bay the O’Malley alliance proved equivocal.

Clew Bay with its host of drowned drumlins, so many islands. A bay with shallow straits, deep channels and strong tidal currents so unpredictable a ship out in the Atlantic would need an O’Malley pilot to guide it to safe anchorage. In the great storm of 21st September 1588, El Gran Grin ran aground off Clare Island and many men were drowned. Of their bones are coral made. Here, right here amongst the drowned drumlins, shipwreck and coral meet. Wave power washes out a coarse gravel of chalky nodules from beds of maerl, a coralline red algae, a calcified seaweed. Like crushed coral, chalky skeletons, brittle branches accumulate in maerl beds for a thousand years. Nearest the light, a purple-pink layer of living maerl grows infinitely slowly, producing oxygen through photosynthesis. Red algae, Rhodophyta. Life-giving maerl beds, a nursery for algae and marine creatures. But it’s a fragile habitat and climate change could disrupt the Rhodophyta.

Skylark are singing as we stop along the Armada Drive to study a map of shipwreck sites, El Gran Grin and San Nicolas Prodaneli wrecked here. A repeated alarm call from the pipit of the place tells us to clear off. Enough of reading information boards! Right now she has young to feed and a beak-full of insect wings and legs to deliver. The imperative of now! Who cares about 1588?

Down to the beach and into the Atlantic Ocean where sunlight refracts through clear, shallow water in coruscating patterns. Starbursts on the sea bed. A mingling of light and shadows. Clusters of shadows float to and fro on rippling waves. What creature makes this drift of shadows? How can there be shadows without substance? Awash on the waves and all about our feet there are transparencies of palest pink. Dirigibles, silk parachutes dragging their shadows. Do they sting, these delicate creatures? With red combs about their amorphous, dilating shapes, are they comb-jellyfish? Once again there are shoals of sea-grass, thousands of tiny fish darting in and out of seaweed rocks. Bizarre and beautiful marine creatures drifting and swimming in the shallows.

Pink parachutes and sea-grass: what a mystery! After the magic, the science, the need to know. It will come, it always does. Travelling light, we had no field guides for the intertidal zones and marine biology, no internet connection. But when we encountered pink parachutes at Clew Bay I ran to fetch my camera. We watched the erratic pulse of waves about the rocks to frame the swimming creatures before they were washed away. Grains of sand showed through the silk of diaphanous parachutes. Shoot the shadows, that was the trick. I brought home a single image of sea-grass. Without it, I could not have made the connection and understood the story unfolding unseen and right before our eyes. A story of loss, and epic as climate change. It is the undertow for our times, and inescapable.

Erris Head and Blacksod Point. The Mullet Peninsula (Barony of Erris).

La Santa Maria Encoronada ran aground at Blacksod Bay. Don Alonso de Leiva fired his ship, marched north, then down the Mullet Peninsula where he knew the Duquesa Santa Ana was undergoing repairs. With an overload of shipwrecked soldiers and mariners on a patched-up vessel they prepared to resume their voyage.

Leaving Achill Island, we follow in his footsteps, travelling around Blacksod Bay and down to the southern tip of the Mullet Peninsula where we plan to overnight. A remote and desolate look-out point to scan the entrance to the bay and involve us in the action, that’s the objective. Remote and desolate is liminal, a threshold into the past, that’s where we’ll come closest to Don Alonso and his men who will have struggled through blanket bog, carrying all they might salvage. How could Erris feed an army, an influx of half-starved vagrants descending like flocks of migrating geese who strip the good grazing and risk the farmers’ wrath?

Hunger stalks Odysseus and his men. Making landfall, they see sleek and healthy flocks on a headland. Bringing havoc to pastoral, they help themselves to cheese, whey and meat stored in a nomadic shepherd’s cave. And Poseidon the Sea God rages to see his son Cyclops blinded, his flocks stolen and driven onto Odysseus’ ships. The Sea God’s anger festers. When the time comes he will avenge his son in elemental fury.

The Mullet Peninsula is low-lying, with mountain vistas. At the north-westerly tip of the peninsula, Erris Head is a place of very high rainfall. We walk an earth-bank, once the parish boundary, toward headland and exposed cliffs where fulmar nest. Thrift and bird’s-foot trefoil at our feet, and a ditch of bright green sphagnum moss. Chough in a geo and gannet out at sea. Underlying its peace and solitude, there’s a welcome in this well-designed walk. Erris is cattle country, lush and fertile. A hospitable farmer, come to feed his black-face ewes and lambs, invites us to camp on his land.

With the landmark of Erris Head in sight, storms on 21st September 1588 drove three merchantmen of the Levant squadron into Donegal Bay where they anchored off-shore until the next great storm drove them onto rocks where they broke to pieces. Captain Francisco de Cuellar could not swim. From the poop of the Lavia, he watched men drowning and saw those who reached the beach set upon by ‘savages’ and stripped naked for the gold coins sewn into their garments. After the storm, the tide cast the bodies of the drowned onto the sands.

The creation of Atlantic storms, the west coast of the Mullet Peninsula is strewn with uninhabited islands, rocks and shoals. We drive west along a track, rocking and rolling through potholes and ruts, bound for the ocean hidden beyond sand dunes thick with marram grass. Skylark sing over machair scattered with daisies and birds foot trefoil. We step clear of sheltering dunes and a blindfold is whisked away to reveal a secluded Atlantic beach with foaming waves beneath a fine sky. Rock pools with crabs and beadlet anemones surround rocks crusted with barnacles and blue-black mussels. We sit on cobbles hurled ashore by Atlantic storms, heaved high up the beach. The peace of the place!

12 June Mullet Peninsula

The North East Atlantic, the reach of the Gulf Stream and the complexity of Continental Shelf currents were unfamiliar to Armada mariners who had no charts for the west coast of Ireland. They calculated their position without regard to the effect of the Gulf Stream, and were disastrously off-course. During those weeks in early September 1588, when Armada vessels sought a safe anchorage in the storms, the Mullet Peninsula must have been in turmoil. Sand dunes gave shelter to fugitives, shipwrecked mariners salvaging what they could carry, uncertain whether the local population would help, or alert the English who feared the Armada would regroup and attack, unaware of the scale of the disaster unfolding all along the west coast.

From our look-out point on a bleak granite headland, exposed to the full force of Atlantic storms, we scan islands and reefs, potential hazards in the entrance to Blacksod Bay. Late afternoon sun glosses the ocean and smoke drifts down by the shore: a turf fire or the firing of La Santa Maria Encoronada? The sky grows dark, wind and rain sweep the headland. After a hot supper, we make all shipshape for the night. During the early hours of the morning the storm magnifies as rain drums and hammers on the roof of the campervan, the wind wrestles us and we rock on Blacksod Point. It’s thrilling, anchored in the lee of a low wall, listening to the ocean and rocking. Imagine those vulnerable Armada vessels close to shore, in fog, in squall and storm-force winds, in darkness. From the shelter of Blacksod Bay, The Duquesa Santa Ana will make her way toward the open ocean. Wait, Don Alonso, wait for the storm to pass. Wait for a lifeline thrown across time. Wait for sea-charts, for longitude, wait for radio and The Shipping Forecast, for a Global Positioning System. Wait for air-sea rescue. We beg you, do not go.

An unexpected Odyssey

Close to Tullaghan Bay, where the Santa Maria Encoronada was wrecked, is the Ballycroy Visitors Centre and they identified my Clew Bay images of pink parachute and sea-grass. Their response opened a window onto marine ecology and research projects across Europe. Pink parachute is carnivorous. Beroe cucumis belongs to the Ctenophora phylum. The transparent creature has eight combs with hairs which beat the waves downwards, creating a shimmering effect. Seen in darkness, it is phosphorescent. (Let's return to Clew Bay at midnight!)

Sea-grass was our secret, our fun find. No one else noticed, not the kids laughing and playing with a beach ball in the shallows. We were enthralled by these marine creatures, but missed the magnitude of the moment and what it signified. How could we guess these slivers of life flickering through the waves were completing their Atlantic Odyssey? Spawned deep in the Sargasso Sea, they drift across the Atlantic Ocean on the strong, warm current of the Gulf Stream on a 5,000 to 6,000 kilometre journey. An awesome migration. They are Leptocephali, eel larvae of Anguilla anguilla, the European eel. Zooming-in on the image, I can make out eyes and a shaded area of internal organs. The salinity of the ocean changes as they approach the shore, they sense the presence of fresh water, and their pack of genetic material is primed to explode. Fresh water triggers metamorphosis and they become glass eels, making their way into the rivers and lakes of Europe as elvers, pigmented and muscularised.

Anguilla anguilla, the European eel, is in trouble. The species is critically endangered, with a decline of 95% in the last thirty years. If the path of the Gulf stream should change, if the current should slow, (from natural or anthropogenic climate change), the eel larvae’s migration would be disrupted. Even if oceanic gyre and current were predictable those shoals of leptocephali have obstacles to overcome; loss of habitat, pollution, over-fishing, barriers of flood defence, with dams, weirs and hydro-electric turbines. How to survive all that!

The tide retreats about the rocky island and the body of a man lies on the shore. Slowly, Odysseus revives. Home to Ithaca at last. He lives, but all his men are lost. He could not save them, their own wilfulness destroyed them. Odysseus’ men ignore every warning when they kill and eat the Cattle of the Sun. Hyperion protests at the outrage. Men must respect the natural order, each day the sun rises and sets upon the sacred herds, upon the earth. No more, he will not. If the gods do not avenge his loss Hyperion will go down to the House of the Dead and stay there! Impossible, the sun must shine. So in thunder and in lightning, in squalls and towering waves Zeus fulminates, Poseidon’s time is come, and Odysseus’ men are lost.

Man’s recklessness unleashes a sequence of extreme-weather events. Oh Lord! What has man done this time? Another anthropogenic disaster, we made it happen. Not everything is mankind’s for the taking.

There is always choice, the poet of The Odyssey tells us, disaster is not inevitable.

What of the European eel? Will Anguilla anguilla be a mass-extinction event? Or can this stark decline be turned around? Protecting the marine environment, establishing no-take zones comes tardily, but it works. Stocks can be replenished.

On dark and moonless autumn nights when Somerset rhynes are brim-full, into King’s Sedgemoor Drain, into the River Parrett swims the mature and thick-bodied silver eel, Anguilla anguilla in its final salt-water metamorphosis setting out to cross the Atlantic to spawn in the Sargasso Sea. Silver eels on migration from the rivers and lakes of Europe. Nocturnal, secretive, swimming deep in the ocean, there are lacunae, disappearances. Two thousand years of mystery surrounds the eel but electronic tagging discovers some of its secrets, charting routes and revealing time-sequences. Understanding the eel’s life-cycle and migratory behaviour is key to reversing its decline. Anguilla anguilla, the European eel. All across Europe there is a sharing of data, a restocking of rivers and lakes, willing the eel’s survival.

From Dooniver Strand and Clew Bay, I came home to Cumbria to discover eel larvae were following me. Eel passes in the River Leven will encourage the return of Anguilla anguilla to Windermere. The heron of Cumbria will welcome their return and take their share, and a pair of otter at Leighton Moss seize either end of an eel and tug.

The North East Atlantic, the reach of the Gulf Stream and the complexity of Continental Shelf currents were unfamiliar to Armada mariners who had no charts for the west coast of Ireland. They calculated their position without regard to the effect of the Gulf Stream, and were disastrously off-course. During those weeks in early September 1588, when Armada vessels sought a safe anchorage in the storms, the Mullet Peninsula must have been in turmoil. Sand dunes gave shelter to fugitives, shipwrecked mariners salvaging what they could carry, uncertain whether the local population would help, or alert the English who feared the Armada would regroup and attack, unaware of the scale of the disaster unfolding all along the west coast.

From our look-out point on a bleak granite headland, exposed to the full force of Atlantic storms, we scan islands and reefs, potential hazards in the entrance to Blacksod Bay. Late afternoon sun glosses the ocean and smoke drifts down by the shore: a turf fire or the firing of La Santa Maria Encoronada? The sky grows dark, wind and rain sweep the headland. After a hot supper, we make all shipshape for the night. During the early hours of the morning the storm magnifies as rain drums and hammers on the roof of the campervan, the wind wrestles us and we rock on Blacksod Point. It’s thrilling, anchored in the lee of a low wall, listening to the ocean and rocking. Imagine those vulnerable Armada vessels close to shore, in fog, in squall and storm-force winds, in darkness. From the shelter of Blacksod Bay, The Duquesa Santa Ana will make her way toward the open ocean. Wait, Don Alonso, wait for the storm to pass. Wait for a lifeline thrown across time. Wait for sea-charts, for longitude, wait for radio and The Shipping Forecast, for a Global Positioning System. Wait for air-sea rescue. We beg you, do not go.

An unexpected Odyssey

Close to Tullaghan Bay, where the Santa Maria Encoronada was wrecked, is the Ballycroy Visitors Centre and they identified my Clew Bay images of pink parachute and sea-grass. Their response opened a window onto marine ecology and research projects across Europe. Pink parachute is carnivorous. Beroe cucumis belongs to the Ctenophora phylum. The transparent creature has eight combs with hairs which beat the waves downwards, creating a shimmering effect. Seen in darkness, it is phosphorescent. (Let's return to Clew Bay at midnight!)

Sea-grass was our secret, our fun find. No one else noticed, not the kids laughing and playing with a beach ball in the shallows. We were enthralled by these marine creatures, but missed the magnitude of the moment and what it signified. How could we guess these slivers of life flickering through the waves were completing their Atlantic Odyssey? Spawned deep in the Sargasso Sea, they drift across the Atlantic Ocean on the strong, warm current of the Gulf Stream on a 5,000 to 6,000 kilometre journey. An awesome migration. They are Leptocephali, eel larvae of Anguilla anguilla, the European eel. Zooming-in on the image, I can make out eyes and a shaded area of internal organs. The salinity of the ocean changes as they approach the shore, they sense the presence of fresh water, and their pack of genetic material is primed to explode. Fresh water triggers metamorphosis and they become glass eels, making their way into the rivers and lakes of Europe as elvers, pigmented and muscularised.

Anguilla anguilla, the European eel, is in trouble. The species is critically endangered, with a decline of 95% in the last thirty years. If the path of the Gulf stream should change, if the current should slow, (from natural or anthropogenic climate change), the eel larvae’s migration would be disrupted. Even if oceanic gyre and current were predictable those shoals of leptocephali have obstacles to overcome; loss of habitat, pollution, over-fishing, barriers of flood defence, with dams, weirs and hydro-electric turbines. How to survive all that!

The tide retreats about the rocky island and the body of a man lies on the shore. Slowly, Odysseus revives. Home to Ithaca at last. He lives, but all his men are lost. He could not save them, their own wilfulness destroyed them. Odysseus’ men ignore every warning when they kill and eat the Cattle of the Sun. Hyperion protests at the outrage. Men must respect the natural order, each day the sun rises and sets upon the sacred herds, upon the earth. No more, he will not. If the gods do not avenge his loss Hyperion will go down to the House of the Dead and stay there! Impossible, the sun must shine. So in thunder and in lightning, in squalls and towering waves Zeus fulminates, Poseidon’s time is come, and Odysseus’ men are lost.

Man’s recklessness unleashes a sequence of extreme-weather events. Oh Lord! What has man done this time? Another anthropogenic disaster, we made it happen. Not everything is mankind’s for the taking.

There is always choice, the poet of The Odyssey tells us, disaster is not inevitable.

What of the European eel? Will Anguilla anguilla be a mass-extinction event? Or can this stark decline be turned around? Protecting the marine environment, establishing no-take zones comes tardily, but it works. Stocks can be replenished.

On dark and moonless autumn nights when Somerset rhynes are brim-full, into King’s Sedgemoor Drain, into the River Parrett swims the mature and thick-bodied silver eel, Anguilla anguilla in its final salt-water metamorphosis setting out to cross the Atlantic to spawn in the Sargasso Sea. Silver eels on migration from the rivers and lakes of Europe. Nocturnal, secretive, swimming deep in the ocean, there are lacunae, disappearances. Two thousand years of mystery surrounds the eel but electronic tagging discovers some of its secrets, charting routes and revealing time-sequences. Understanding the eel’s life-cycle and migratory behaviour is key to reversing its decline. Anguilla anguilla, the European eel. All across Europe there is a sharing of data, a restocking of rivers and lakes, willing the eel’s survival.

From Dooniver Strand and Clew Bay, I came home to Cumbria to discover eel larvae were following me. Eel passes in the River Leven will encourage the return of Anguilla anguilla to Windermere. The heron of Cumbria will welcome their return and take their share, and a pair of otter at Leighton Moss seize either end of an eel and tug.